Mainstream biology continues to insist that calcium is essential to bone strength and structure, but its time we dig into this assumption and reframe the question.

What if bones aren't structured because of calcium, but are instead primarily a place where the body stores excess calcium to keep it out of circulation and protect more vulnerable cells from calcification?

Rather than calcium building or strengthening bone, what if calcium is stored in bone to keep it away from soft tissues and circulation, much like the liver isolates toxins, or fat stores hold on to environmental pollutants.

Traditionally, we’re told that calcium is vital for bone because it combines with phosphate to form hydroxyapatite crystals - the stuff that supposedly gives bones their hardness. Bone cells, osteoblasts and osteoclasts, constantly rebuild and break down bone tissue in a process we’re taught depends heavily on calcium.

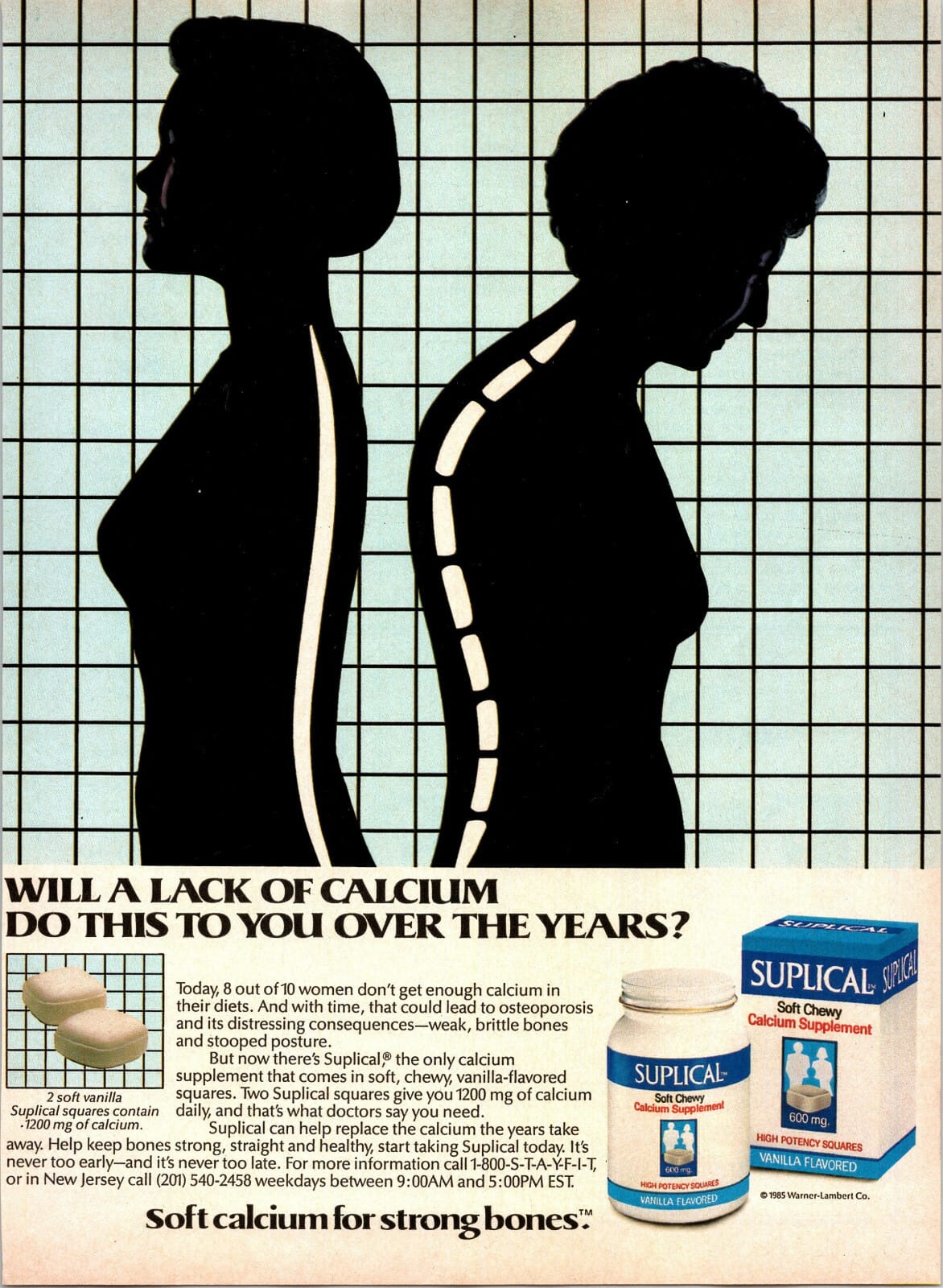

We've been told that this is why calcium supplementation is so important. Without proper calcium supplementation, our bones can't rebuild themselves and so we become prone to osteoporosis and bone fracture.

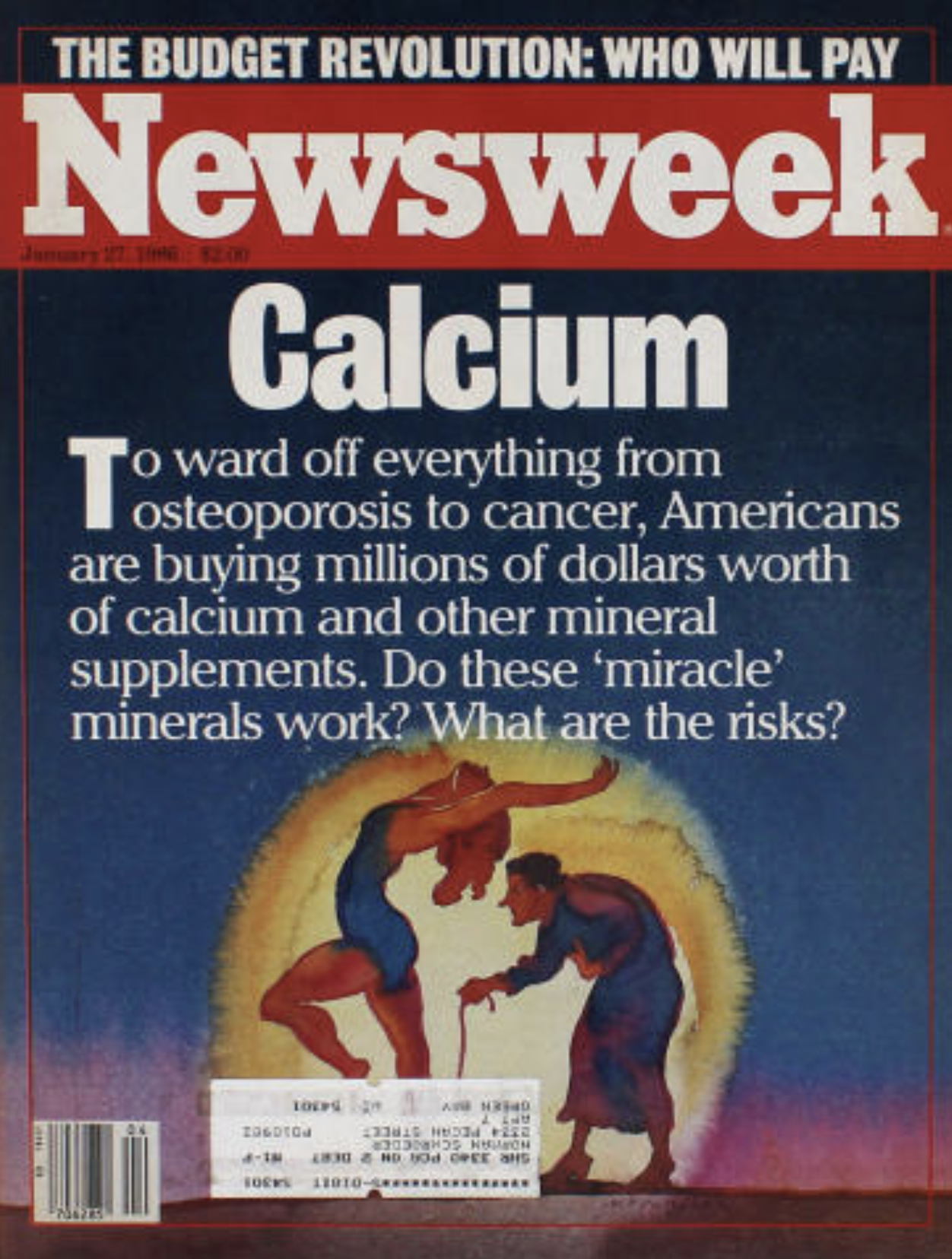

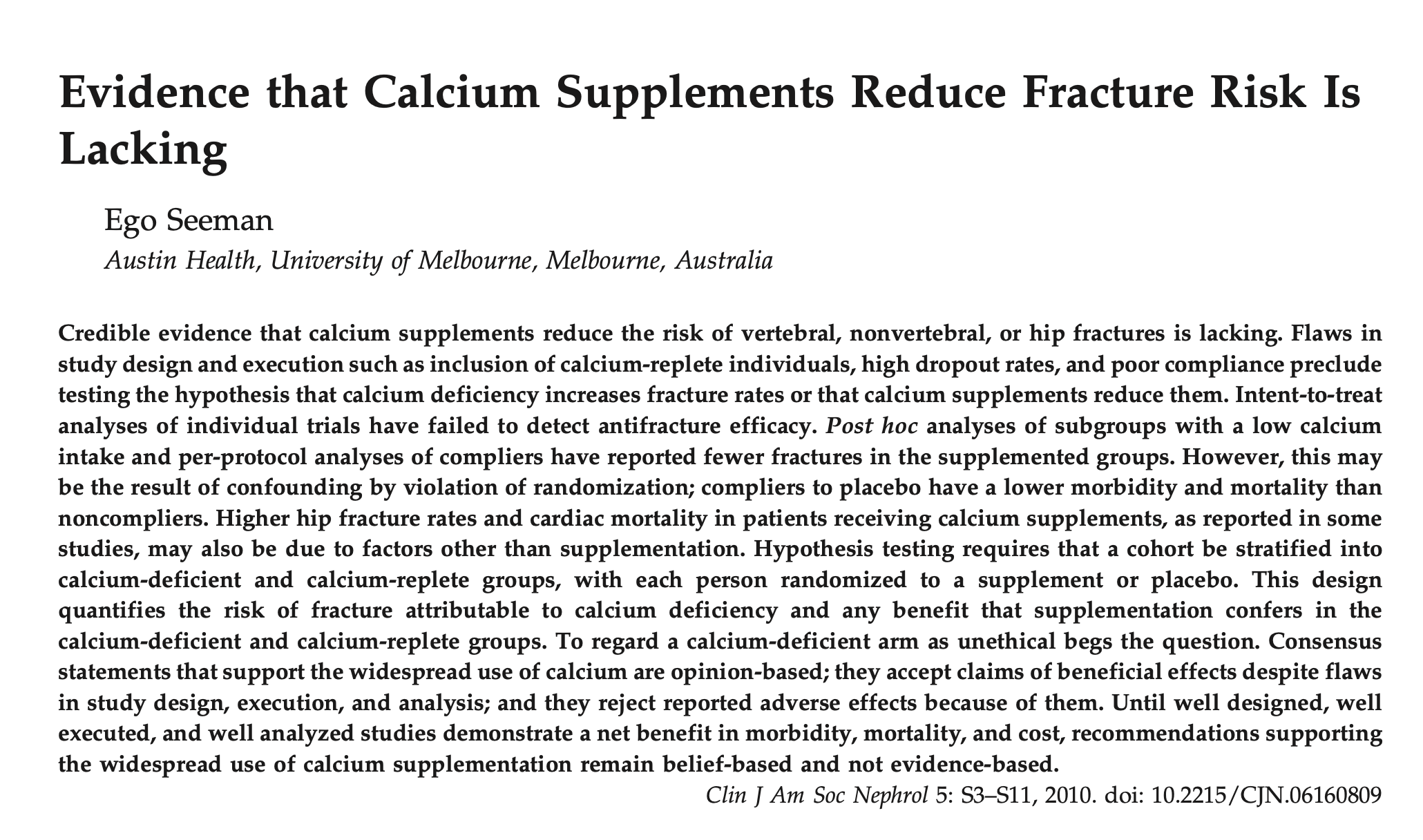

This calcium supplementation narrative has continued to exist for the past 40 years, despite INSANE amounts of evidence to the contrary.

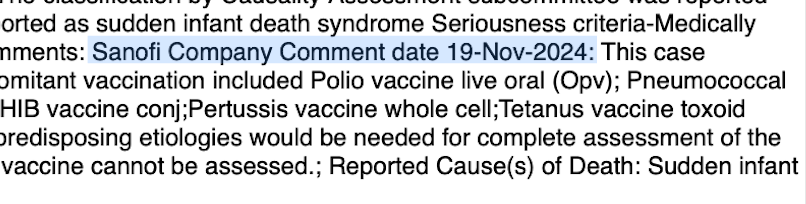

Here are 10 studies which found that calcium supplementation actually did NOTHING to improve bone health or reduce bone fractures, but did in fact increase risk of death from heart disease, GI distress, kidney stones and liver harm:

- "Our findings suggest that high intake of supplemental calcium is associated with an excess risk of CVD death."

- "Calcium supplement use may increase the risk for incident coronary artery calcification."

- "Calcium supplementation in healthy postmenopausal women is associated with upward trends in cardiovascular event rates. This potentially detrimental effect should be balanced against the likely benefits of calcium on bone."

- "Calcium supplements cause gastrointestinal side effects, particularly constipation, and increase the risk of kidney stones and, probably, heart attacks by about 20%."

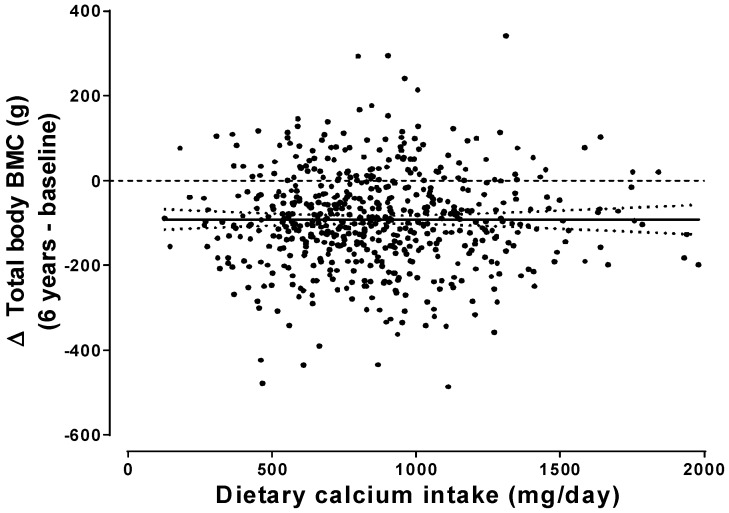

- "Taking calcium supplements produces small non progressive increases in BMD, which are unlikely to lead to a clinically significant reduction in risk of fracture."

- "These data support the hypothesis that calcium tablets increase the incidence of adverse GI events."

- "Combining this recent finding with available data associating calcium supplementation with cardiovascular mortality and all-cause mortality, we call on the need for an evidence-based approach to calcium supplementation, while stressing on the safety of dietary calcium intake over the former on cardiovascular health."

- "Calcium supplementation was present in the groups with hypertensive pregnant women."

- "Ca supplements do not provide a benefit to overall Ca metabolism or bone characteristics and that the amount of Ca consumed is of greater influence in enhancing Ca nutrition and skeletal strength."

- "A recent meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials showed that calcium supplementation was not associated with a low risk of fractures among community-dwelling older adults. There has been a concern for a significant increase in the risk of cardiovascular diseases with high supplemental calcium intake." [PubMed: The good, the bad, and the ugly of calcium supplementation: a review of calcium intake on human health]

"Ask anyone how to prevent bone fractures and they're likely to answer, "Get more calcium." Medical experts have tended to agree. For example, the Institute of Medicine advises a calcium intake of 1,000 to 1,200 milligrams (mg) a day for most adults. But in the last five years, we've also learned that calcium — at least, in the form of supplements — isn't risk-free. An intake of 1,000 mg from supplements has been associated with an increased risk of heart attack, stroke, kidney stones, and gastrointestinal symptoms.

Now an analysis of reams of research concludes that consuming calcium at that level doesn't even reduce fractures in people over 50. And a related analysis indicates that increasing calcium intake has only a modest effect on bone density in people that age. Both were published online this week in the medical journal BMJ."

The bones are like a kind of vault, storing whatever calcium isn’t being actively used elsewhere. And when levels drop, the body draws on those reserves.

That would explain why people with low calcium intake often develop osteoporosis, it’s not that calcium is missing from the diet so the bones can’t be built, it’s that the body is pulling calcium from the bones to keep the rest of the system functioning.

Discussion